Do you know anyone who claims to be against government and for business? What most people mean when they say this is that they’re against bad government.

This type of thinking tends to create an anti-government mentality that portrays any type of government as ineffective. And for those that hold this anti-government viewpoint, they’re also often against any type of community planning, whether it’s land use planning, infrastructure planning, or economic development planning.

This viewpoint is understandable because there are plenty examples of ineffective government and poor planning. And even though there are also many examples of good government and good planning, the negative examples are the ones that dominate the headlines.

It’s almost like we have a national addiction to negativity. Turn on the local news and what do you see? Murders, car crashes, outbreaks of infectious disease…and so on. And it’s not just popular culture and mainstream media. The realms of business and science fall prey to this obsession with negativity as well. In fact, as recently as 1998, there was a 17-to-1 negative-to-positive ratio of research studies in the field of psychology. This means that for every study about what makes people thrive and be happy there were 17 studies on depression and disorder. Fortunately, this is changing thanks to the positive psychology movement. Harvard University’s Shawn Achor covers this in his book The Happiness Advantage.

Just like the positive psychology movement sought to study what works instead of only studying the negative side of the human mind, I want to change the national conversation about government. Instead of just looking at what’s broken, we should seek out government initiatives that make our cities more vibrant. And we should learn from these examples to apply these lessons in more communities.

So for the next few minutes, join me in a brief exploration of how the government is supposed to function. Below are are 3 shining examples of good government.

Good Government Example #1

The Choice Neighborhood Program

Let’s start by looking at public housing policy at the federal level. This is a perfect example to start with because it used to symbolize bad government at its worst.

The negative impacts of the massive “tower-in-the-park” housing projects built in large cities in the 1950s-1970s have been widely reported. And rightly so. This was a comprehensive failure by the federal government and, to a lesser extent, many state and local governments. They failed to anticipate all of the negative impacts of large-scale public housing.

Now, fast-forward 50 years. The federal government, through HUD (the Department of Housing and Urban Development) has done a 180-degree shift, moving entirely away from creating large-scale public housing projects to its current philosophy of small-scale, mixed-income neighborhood development. This is embodied in HUD’s Choice Neighborhood program.

The Choice Neighborhood program is centered on 3 goals:

- Housing: Replace distressed public and assisted housing with high-quality mixed-income housing that is well-managed and responsive to the needs of the surrounding neighborhood;

- People: Improve educational outcomes and intergenerational mobility for youth with services and supports delivered directly to youth and their families; and

- Neighborhood: Create the conditions necessary for public and private reinvestment in distressed neighborhoods to offer the kinds of amenities and assets, including safety, good schools, and commercial activity, that are important to families’ choices about their community.

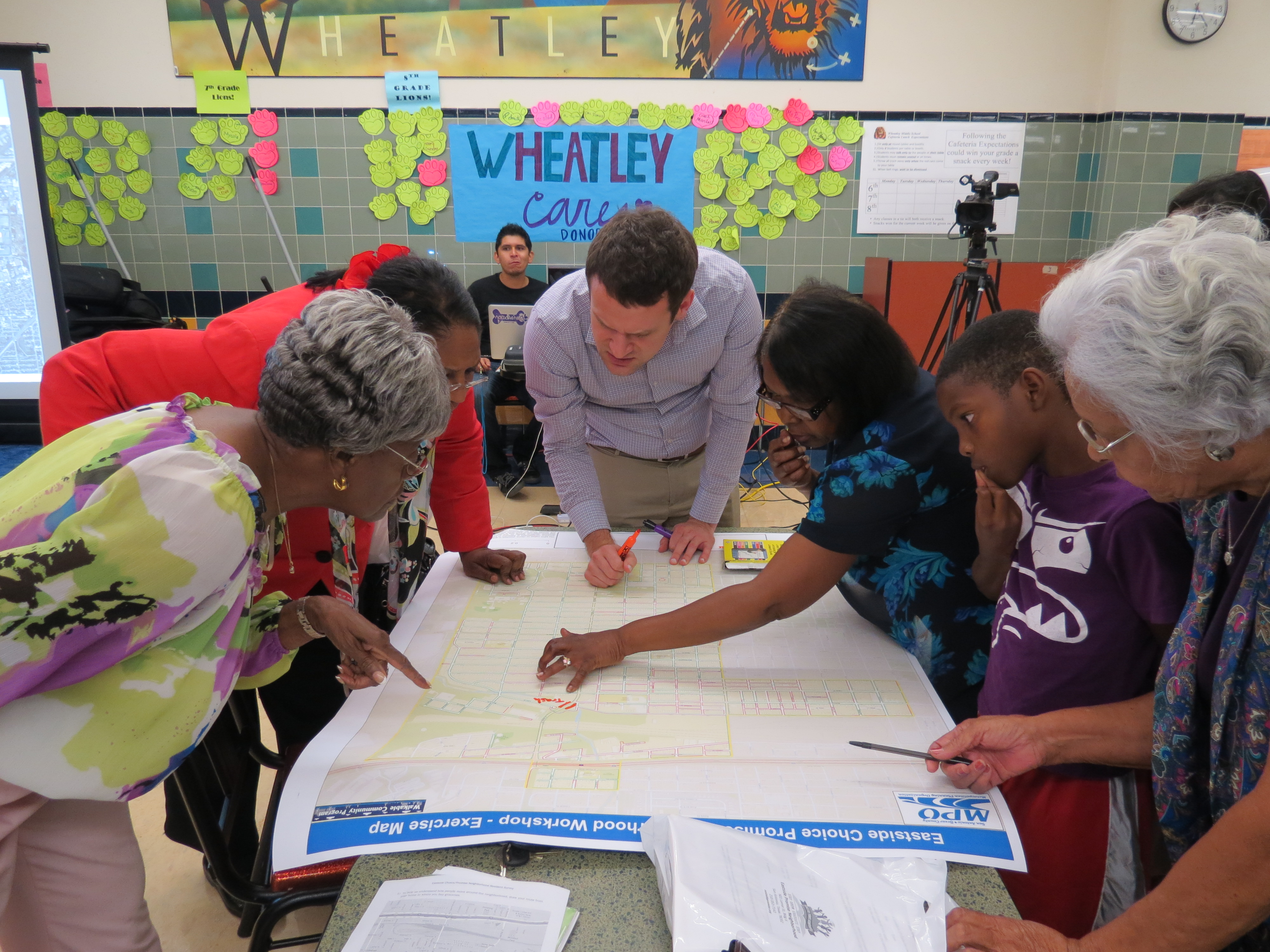

I was fortunate enough to be involved in a successful application for a Choice Neighborhood implementation grant for the Wheatley Courts neighborhood in San Antonio. Wheatley Courts is a public housing development built in the 1940s with a surrounding neighborhood that is arguably the most disadvantaged neighborhood in the entire San Antonio region.

The median annual income for households in the Wheatley Courts neighborhood is only $5,000, compared to a citywide median household income of about $45,000. The neighborhood has less than 1% of the region’s population but accounts for 9% of the region’s violent crimes. The neighborhood is filled with vacant lots, boarded-up homes, and stray dogs.

Oh, and I almost forgot to mention that the housing units in the public housing complex itself don’t have air conditioning. And just for the record, we’re talking about San Antonio, Texas, not San Antonio, Colorado (yes, there’s actually a tiny settlement in Colorado by the name of San Antonio). San Antonio sits in the heart of South Texas, a place where month-long stretches of 100-degree heat are not uncommon. So, clearly this is a situation that needs to change. And it will change.

The San Antonio Housing Authority (SAHA) was awarded a $29.75 million grant from HUD to remove the obsolete public housing and replace it with a mixed-income neighborhood. Which brings me to my favorite aspect about the Choice Neighborhood program: it’s a contest. Not a contest based on random luck like the lottery. It’s a contest based on 2 factors: 1) need and 2) likelihood for success. Wheatley Courts obviously satisfies the first factor…what about the second?

Out of 42 national applicants, only 4 projects were selected. Wheatley Courts was chosen not only because of its needs…there are thousands of public housing developments across the U.S. in bad shape and in need of redevelopment. It was awarded the grant money because of the ongoing efforts of SAHA, the city of San Antonio, and several non-profit community organizations. It was chosen based on its potential for redevelopment given its proximity to two growing employment centers (Fort Sam Houston and downtown San Antonio) and nearby neighborhoods that are revitalizing. It was also selected because the surrounding neighborhood was the recipient of a $24.6 million Promise Neighborhood grant from the U.S. Department of Education. The Promise Neighborhood program is designed to significantly improve the educational and developmental outcomes of children and youth in distressed communities.

Wheatley Courts is the only neighborhood in the U.S. that was awarded an implementation grant for both the Choice Neighborhood program and the Promise Neighborhood program. In summary, HUD decided that Wheatley Courts deserves the $29.75 million investment because it has strong potential to transform itself into a vibrant community.

The Choice Neighborhood program isn’t perfect – nothing about urban vitality is ever perfect – but it is unquestionably a vast improvement over the public housing policies of the past. The U.S. government should be receiving widespread praise for the good government and good planning it is doing to improve urban neighborhoods.

Good Government Example #2

Regional Tax-Base Sharing in the Twin Cities

Note: this example is partly based on an excerpt from my eBook, The 10 Traits of VIBRANT Cities.

True collaboration in metro areas – where each city sacrifices a bit for the benefit of the region as a whole – is a rare sight. The Minneapolis-St. Paul metro area offers the best example of true regional collaboration: the Fiscal Disparities regional tax-base sharing program. This program, authorized in 1971, takes 40 percent of the commercial-industrial tax base growth from the region’s 7 core counties and redistributes the money to local governments across the entire metro area to reduce inefficient competition for tax dollars.

Other benefits of the Twin Cities Fiscal Disparities program include: increased joint economic development efforts, improved regional land-use planning, stable regional growth patterns, and lower tax rates and service inequalities. A couple other notable examples of regional tax-base sharing include the New Jersey Meadowlands Commission Inter-Municipal Tax Sharing Program and the Pittsburgh region’s Allegheny Regional Asset District.

The Minneapolis-St. Paul region’s “we’re-all-in-this-together” style of economic development is a perfect illustration of how communities can combat the economic principle known as the “tragedy of the commons”, a concept which dates back to English villages in the early 1800s.

What is the tragedy of the commons? As the Industrial Revolution took hold in England, the demand for wool grew exponentially. In English villages, shepherds often grazed their sheep in common areas. For each individual herder, it made sense to allow all of his sheep to graze from the commons, while the village as a whole suffered from over-grazing of the commons. If each herder in the village allowed all of his sheep to graze in the common, this set of individually rational economic decisions could lead to the deterioration or complete destruction of the common, a bad economic outcome for the entire village and for each of the individual herders. And for the sheep? Well, they all thought it was a b-a-a-a-a-a-a-a-d decision.

Chances are pretty good that your metro area is suffering from the modern day version of the tragedy of the commons: the fight for tax dollars. The most prevalent example of this battle is the competition for new shopping centers within a metro area. These battles are often fierce, because the city that wins a new development will reap the rewards that come in the form of increased sales tax and property tax revenue. But your metro area as a whole doesn’t benefit from this. Even worse, some of the cities in your region are probably spending a lot of time and money actively competing against their neighbors for new economic development projects (retail centers, office parks, industrial developments) that will add to their tax base. These resources could instead be focused on activities that will enhance the economic vitality of your region as a whole.

Ultimately, the individual communities that make up an urban region must understand that they have a shared destiny. True collaboration is an essential ingredient for success if you want your region to avoid an outcome similar to the tragedy of the commons. All else equal, metro areas that establish collaborative public policies have the best shot at becoming vibrant regions.

Good Government Example #3

Closure of Broadway in Times Square

Times Square, New York, NY (Photo from NYCDOT)

I really lucked out with my first “real job” after grad school. My wife and I moved to New York in May 2008, right after completing my Masters studies. The official reason for moving was my wife getting accepted to NYU for her graduate studies in educational psychology…but in reality, we were tired of living in suburbia and being dependent on driving everywhere. More than anything, we were ready for an adventure.

Our adventure began with a cross-country road trip in a small moving truck from San Antonio to NYC with a handful of belongings and one of our two dogs. Our destination, a 250 sq. ft. apartment in the West Village, only allowed one dog, so we had to leave our other dog with family in Texas for our first year in New York.

After a long, exciting summer of job-searching, interviewing, and exploring my new surroundings, I finally landed a job in late September with the New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT) in their relatively new Division of Planning & Sustainability.

NYCDOT was involved in a bunch of really innovative things when I arrived in December 2008. By the way, this isn’t a typo…the time between hire date in September to start date in December was actually “quite fast” as many colleagues observed. Later on, I learned that the red tape involved in the city’s hiring process often led to cases of 6+ months from hire date to start date, longer than most people can realistically wait to begin a new job.

In any case, my small section of the 5,000 employee agency – the Division of Planning & Sustainability – had a staff of about 40 people. And we were the lucky ones to dream up and test out some of the coolest projects in the realm of transportation planning and policy. Our division was in charge of things like: Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), pedestrian plazas, variable rate parking pilots, public art, alternative fuels, and freight mobility planning. I ended up working in the division’s Office of Freight Mobility, which was an incredible experience. But the most exciting thing NYCDOT did during my time there was the transformation of Times Square into a pedestrian-only zone.

When I first heard of the idea, it sounded crazy to close Broadway through Times Square. But the more I thought about it, the concept made perfect sense. Here you had the most crowded part of the most crowded city in the U.S. During rush hour, which is practically 24/7 in Times Square, it was impossible to walk on the sidewalk without rubbing shoulders – literally – with dozens of other pedestrians. The sidewalks along Broadway were about as packed as the subway cars below ground. Not to mention the several lanes of traffic filled with cars, buses, and taxis at all hours. Which led to an important question…

Did the vehicles really need to be there? That’s the question asked by Janette Sadik-Khan, NYCDOT commissioner at the time. The only way to answer this question was to implement a pilot project that closed the street from traffic for over a handful of blocks in the busiest pedestrian zone in the city. And that’s exactly what happened.

For a one-year trial run, Broadway was closed from 42nd Street to 47th Street in Times Square, and also from 33rd Street to 35th Street in Herald Square. The street was off-limits to vehicles and hundreds of lawn chairs were placed throughout Times Square. And NYCDOT meticulously measured the impacts of this closure on pedestrians and on traffic.

What were the results of the Broadway closure? The world didn’t end. Traffic didn’t skyrocket in Midtown Manhattan. And Times Square didn’t lose business as many had feared. In fact, Times Square and Herald Square gained more pedestrians, all of which was good news for the businesses in both public spaces.

Here are just a few highlights from the Broadway closure in Times Square (here’s a report with more detailed findings from the pilot project):

- Bus travel speeds increased by 13% on Sixth Avenue and fell by 2% on Seventh Avenue.

- Injuries to motorists and passengers in the project area are down 63%.

- Pedestrian injuries are down 35%.

- 74% of New Yorkers surveyed by the Times Square Alliance agree that Times Square has improved dramatically over the last year.

- The number of people walking along Broadway and 7th Avenue in Times Square is up 11% and pedestrian volume is up 6% in Herald Square.

Bottom Line

Here are the 3 principles of good government that all public entities should follow if they want to function as a positive force for vibrant cities:

- Act more like businesses. Governments should evaluate major spending and public policies as investment opportunities. HUD viewed the Wheatley Courts neighborhood as a valuable investment, not as a hopeless welfare recipient. NYCDOT viewed its city streets as an asset to be invested in and it has paid off.

- Pay close attention to what works and what doesn’t work. This is something that all successful businesses also do. Governments should measure the results of their actions. More importantly, they should use this knowledge to keep doing what’s working and try something different when things aren’t working.

- Avoid the tragedy of the commons. Collaboration among separate government entities, especially within a single metro area, is a powerful tool for progress. The simple decision to stop competing with neighboring communities for resources opens up a wide range of new opportunities for regional economic development and enhanced urban vitality.

Do you have any examples of good government in your community? Let me know in the comment section.

Leave a Reply