This post is all about why traffic congestion is a good thing for your city. If you’re looking for advice on how to get rid of the traffic jams that take place every day on your city’s highways, you’re in the wrong place.

Here goes…

Traffic Truth #1- Bad traffic is just a symptom of your city’s economic success.

Traffic Truth #2- Traffic congestion is actually a good thing for urban vitality.

Traffic Truth #3- Efforts to reduce traffic congestion are counter-productive.

Traffic Truth #4- Ignoring your city’s traffic problems will help you create a more vibrant community.

This post is partly based on an excerpt from my eBook: The 10 Traits of VIBRANT Cities.

Traffic Truth #1: Bad traffic is just a symptom of your city’s economic success.

Bad traffic is great for cities, large cities in particular. Wait! Don’t shoot me just yet! Let me explain. I hate sitting in traffic just as much as you do. Bad traffic sucks, at least when you’re driving in it. However, as miserable as it is to drive in bad traffic, this is actually a sign that your city is doing something right.

Traffic congestion is just a symptom of a city that has a strong, growing economy. The most effective way to get rid of your city’s traffic problems is to kill your city’s economy. Doesn’t sound very appealing does it? Just take a look at cities with astronomical unemployment rates that have lost a large amount of jobs and residents in the last few decades. Here’s a Huffington Post article on “shrinking cities”. You won’t find yourself stuck in a traffic jam in these cities, but good luck getting a job, starting a successful business, or even enjoying an evening stroll along an active urban corridor.

Traffic Truth #2: Bad traffic is actually a good thing for urban vitality

Okay, so maybe it’s not that that hard to see that traffic congestion is a side effect of a healthy, growing city. But, I said bad traffic is a good thing, right? That’s right. Traffic congestion is a huge opportunity disguised as a problem. Don’t waste that opportunity by expanding your city’s highways to accommodate (and thus, create) more traffic. The biggest opportunity provided by traffic congestion is that it encourages the development of a more complete transportation network, ultimately improving the accessibility of your city.

Here are 3 reasons why traffic congestion is good for your city, if you want to make your city more vibrant:

1. Traffic congestion causes people to live closer to their jobs to avoid long commutes. And by closer, I mean not just less time involved in the commute, but physically closer. This leads to higher densities of development, a greater concentration of residents living in or near downtown and other major employment centers, and a more diverse mixture of land use patterns, especially downtown….all good things for urban vitality. More on the importance of downtown residential development and land use diversity here.

2. Where bad traffic exists, it leads people to consider other modes of travel beyond driving. No one enjoys wasting time in stop-and-go traffic on a highway. Of course, there are some things you can do to lessen the pain/stress of bad traffic: music, audiobooks, cursing at your fellow highway-goers. Okay, maybe that last one will actually increase stress levels, not just for you but for everyone. But, it’s just as important to point out some of the things that you cannot do while you’re stuck in traffic: work on a laptop, sleep, relax and enjoy the scenery, engage in a friendly conversation with fellow freeway travelers, etc. When faced with extreme traffic congestion on a daily basis people naturally begin to consider other travel modes (transit, walking, biking) and different living arrangements (moving closer to their job/business or to a more urban location) to support those travel modes.

3. Traffic congestion makes city streets safer for everyone. And this is a very good thing for urban vitality. It’s much safer and more pleasant for pedestrians to walk on sidewalks adjacent use roads where cars are traveling at 10 or 20 mph compared to roads where cars travel at near-highway speeds of 40 or 50 mph. And slower travel speeds are safer for drivers too, of course. Traffic congestion (and other “traffic calming” strategies) on urban streets cause drivers to become more aware of and engaged in the streetscape. This has played a big role in New York’s recent success as the safest large U.S. city for pedestrians.

Traffic Truth #3: Efforts to Reduce Traffic Congestion are Counter-Productive

This is going to be controversial, but I’m going to say it anyway: We do not need to build any more highways in large U.S. cities, period. In fact, many of our existing urban expressways need to be removed entirely. And we certainly do not need to be expanding our urban expressways.

Building more highways, and expanding our existing highways will ultimately lead to one thing: more traffic. Of course, we can’t just do away with all existing highways. Highways are a necessary evil, after all. We do need a limited amount of highways for long distance travel and to accommodate trucks. We all like to eat on a daily basis, right? Okay, so we can’t just do away with trucks and the goods that they deliver. And trucks need highways to operate efficiently. But, if you look at the typical traffic mix on any given highway in U.S. cities, trucks typically account for less than 5% of the total traffic, almost never more than 10% of the total traffic. In fact, according to Federal Highway Administration data, passenger vehicles account for more than 95% of all highway traffic.

Anyone responsible for managing and improving a city should not be focused on traffic. Especially in large cities. The amount of money, time, and mental capacity spent by all governments (local, state, and federal) in the name of traffic reduction is enormous.

According to a study from the U.S. Federation of State Public Interest Research Groups (PIRG), since 1956 – the year that the Federal Highway Act was passed, more commonly known as the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act – governments at all levels have invested nine times more funds in highways than in transit.

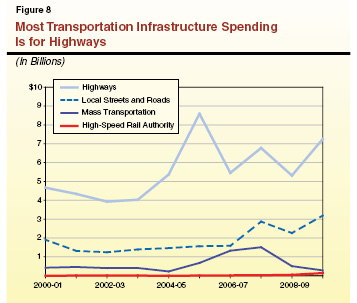

These two graphs show the stark contrast between highway spending and transit spending:

And what’s the result of all this highway spending? More traffic! Yes, that’s right. And it’s not complicated, if you think about it. Expanding the highways of a large, growing city to handle more traffic will simply allow the same highway to handle more traffic.

As your city grows over time, this increase in traffic will create more congestion. Los Angeles is a perfect example of this. LA has successfully created the largest, most expensive regional highway system in U.S. history. And what does LA get in return? The worst traffic congestion in the country.

A single-minded focus on highway expansion will short-change your city’s residents because they will still be left with only one option for getting around: driving. This article from Eric Jaffe over at The Atlantic Cities provides a good explanation (backed up with research) of why simply building more roadway facilities does not ease congestion. Oh, and by the way, even in California (one of the more transit-friendly “blue” states) highway spending far outweighs transit spending. See the graph below.

My recommendation to stop focusing on ways to reduce traffic congestion even applies to the promotional efforts for construction of new transit lines (light rail, streetcar, commuter rail, etc.). In many communities, major transit investments are only possible through a referendum in which the residents of a city must agree to pony up the money for the new transit line. And the most common selling point used by boosters to try to convince voters of the benefits of the new transit line is that it will reduce traffic congestion. Unfortunately, this is usually not true. See this article from Clark Williams-Derry, Deputy Director of the Sightline Institute (a think tank focused on sustainable solutions for the Northwestern U.S.), which cites multiple studies that have shown transit investments have little or no impacts on reducing traffic congestion. Williams-Derry concludes his article with this statement about transit:

Transit is good for an awful lot of things. It helps move people to where they want to go; it gives people who prefer not to drive, or who can’t drive, a decent transportation option for many trips. It can reduce a region’s reliance on risky fossil fuels; and on and on. But for folks who hope that transit investments will offset the impacts of road expansions—well, sadly, I don’t think the evidence lines up that way.

Aside from the fact that transit is not guaranteed to bring about a decline in traffic congestion, there’s another reason why transit advocates should refrain from this promise in promotional efforts: it’s simply not effective. Why? Because voters in big cities are accustomed to hearing false promises of “traffic reduction”. Time after time, when a new highway is built or an existing highway is expanded, the promised decline in traffic doesn’t appear. The only thing that appears is more cars. For a clear explanation of why traffic congestion is not a good indicator of the success of a transit expansion, see this post by Jarrett Walker, international transportation consultant and author of Human Transit: How Clearer Thinking About Public Transit Can Enrich Our Communities And Our Lives.

Traffic Truth #4: Ignoring your city’s traffic problems will help you create a more vibrant community.

So, what should policy makers and local governments do about traffic congestion? Nothing. I’m not saying that now you should start creating bad traffic on purpose. What I am saying is that cities have been focusing on the wrong thing. You get what you focus on. If you focus on dealing with traffic congestion and highways, you’ll inevitably end up with more congestion and more highways.

If you have bad traffic in your city, simply accept this as a fact of life and make the conscious choice to stop building more highways, expanding roads, and trying to speed up traffic. Instead, save your efforts for more productive pursuits like expanding your city’s transit system and making investments that enhance your city’s walking and biking infrastructure. In the end, fighting against bad traffic is not only futile; it’s actually counter-productive if you’re trying to make your community more vibrant.

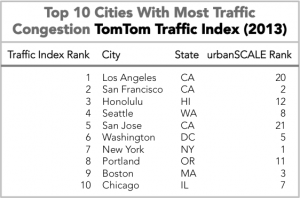

If you’re still not buying into this line of thinking, that’s understandable. It may be difficult to accept a new idea that is entirely opposed to the conventional wisdom about how cities are supposed to function. The good news is that you don’t have to take my word for it. Just look at the table to the below, which shows the top 10 U.S. cities with the worst traffic congestion according to the TomTom Traffic Index, along with each city’s urbanSCALE rank.

A city’s urbanSCALE score is essentially a measure of how vibrant that community is. If you’re interested, you can find out more about the urbanSCALE Rating System. It turns out that the most congested cities are also among the most vibrant cities. Despite the bad traffic (and in part, because of it), these cities have managed to become vibrant communities. It doesn’t look like traffic congestion is really the boogieman that it’s made out to be, does it?

Portland, OR – one of the many cities that rank very high in both traffic congestion and urban vitality – offers us an example of a different approach. Portland has really gone against the grain with its anti-highway culture. In the 1960s – a time when pretty much every large U.S. city was busy tearing down urban neighborhoods to build expressways – Portland cancelled the planned Mount Hood Freeway, a highway that would have demolished the homes of thousands of residents. And in the 1970s – when most big cities were still building urban expressways – Portland became the first major city to actually tear down a highway, Harbor Drive, replacing it with a downtown waterfront park.

Now fast-forward to present-day Portland. What are the results of the city’s anti-highway efforts? Portland has the highest percentage of bicycle commuters (5.8% of all commuters) among the 100 largest cities and also a high percentage (5.1%) of commuters that walk to work, better than 82 of the 100 largest cities.

So, what about the rest of the U.S.? What does the current state of affairs look like for highway spending vs. transit spending? Thankfully, Larry Ehl, publisher of Transportation Issues Daily, has created a summary cheat sheet of the current federal transportation legislation known as MAP-21 (Moving Ahead for Progress in the 21st Century).

Unfortunately, the 80/20 split (80% of dollars going to highways and 20% for transit) remains unchanged from the previous legislation. MAP-21 includes $40.4 billion in highway funding for FY 2013, compared to $10.5 billion in transit funding. FY 2014 includes $41 billion for highways and $10.7 billion for transit.

Now, imagine for a minute that highway funding and transit funding was 50/50 instead of 80/20 for a total of about $26 billion for highways and $26 billion for transit. This would translate into an additional $15 billion in annual transit funding. Wow! If this continued for a 10-year period, this would result in an extra $150 billion for transit. Wow times 10! What could actually be accomplished with these additional funds? Let’s do a fun little exercise to really get a sense of how much could be achieved if highway/transit funding was on a level playing field.

Imagine a future where highway and transit funding is balanced at 50/50

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, as of 2012, roughly 85% of the nation’s population lived in metro areas (267,664,440 people in metro areas out of the total 313,873,685 U.S. residents). For our exercise, we will assume that all of the $150 billion in extra transit funding will go to these areas since public transportation is essentially only takes place in cities as opposed to rural areas.

This would provide $560.40 of additional transit funding for each person living in a metro area over the 10-year period. But this figure doesn’t really tell us anything useful, right? So, let’s look at what this would mean for a few actual places. We’ll look at one smaller metro area (population around 500k), one mid-size metro area (population around 2 million), and one large metro area (population of 5 million or more).

Here’s what the future could look like 10 years from now in 3 metro areas if highway funding and transit funding were equalized:

1. Lexington, KY (2012 metro area population: 485,023)

Under the 50/50 highway/transit funding scenario, the Lexington region would receive $272 million ($271,808,425.50 to be exact) in transit funding, above and beyond what they already will receive.

Let’s assume that Lexington would use the money to build a new streetcar system. How many miles of streetcar lines could the $272 million actually buy? Well, the average cost of streetcar lines currently under construction in the U.S. is about $46 million/mile, so Lexington could expect about 6 miles of new streetcar lines. (Special thanks to Yonah Freemark, Founder of The Transport Politic, for providing this data.)

With this money, Lexington could build a streetcar system with 2 lines that connect downtown to multiple surrounding neighborhoods. This new streetcar system could also easily connect the city’s two most important districts: the downtown core and the nearby University of Kentucky campus.

2. Austin, TX (2012 population: 1,834,303)

The 50/50 funding scenario would provide the Austin metro area with over $1 billion ($1,027,949,211.33) in new transit dollars. Austin is currently planning an “urban rail” (likely light rail, but possibly with some streetcar elements) system for the city’s urban core. The first phase of this system, as currently envisioned, is a 7.5-mile corridor that would begin in Austin’s central business district and would travel north to the state capital complex, the University of Texas campus, and ultimately would connect to urban neighborhoods north of the campus.

How much would this cost? The average cost per mile of similar light rail systems under construction right now is about $113 million. With $1 billion in new transit funding, Austin could pay for the entire cost of Phase 1 and even make a sizable down payment on Phase 2 of its urban rail project, a line that connects downtown to the Austin-Bergstrom International Airport via Riverside Drive.

3. Atlanta, GA (2012 population: 5,457,831)

The Atlanta region would gain more than $3 billion ($3,058,585,780.02) in additional transit investments if the 50/50 funding scenario were a reality. Unlike the other two cities in our previous examples, Atlanta already has a fairly substantial rail transit system. The MARTA metro rail system consists of four lines that run a total of 47.6 miles. And Atlanta is currently building a 2.7-mile downtown streetcar line.

So, let’s assume that Atlanta now wants to build a citywide light rail system to complement its other transit investments. Using the same $113 million/mile construction costs for light rail as we did in the Austin example, Atlanta’s $3 billion of new transit funding would pay for 27 miles of new light rail lines. This investment would increase the total length of Atlanta’s existing rail system by 57%.

Bottom line: It’s time to change the conversation about traffic congestion

In the end, you need to change the conversation about traffic congestion in your community if you want public decisions about transportation lead to positive outcomes for your city’s urban vitality. I’ll leave you with a quote from this report by Todd Litman, Founder & Executive Director of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute and a prolific blogger over at Planetizen. Litman ends his extensively researched report with a summary of how the traffic congestion dialogue typically plays out today and how it could be framed in the future in a more helpful manner:

If you ask people, “Do you think that traffic congestion is a serious problem?” they frequently answer yes. If you ask, “Would you rather solve congestion problems by improving roads or by using alternatives such as congestion tolls and other TDM (Transportation Demand Management) strategies” a smaller majority would probably choose the road improvement option. This is how transport choices are generally framed. But if you present the choices more realistically by asking, “Would you rather spend a lot of money to increase road capacity to achieve moderate and temporary congestion reductions and bear higher future costs from increased motor vehicle traffic, or implement other types of transportation improvements?” the preference for road building might disappear.

What do you think? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

You really need to read up on Austin’s proposal. It’s headed to one of two disappointingly low density speculative developments, NOT the city’s key urban neighborhoods where transit ridership is easy.

M1EK-

You’re referring to the Mueller development and the Highland Mall/Austin Community College campus mixed-use development I assume? Where would you place Austin’s first rail line, if it was up to you? By the way, I had included a link to an older proposal. The Austin section now includes a link to Project Connect and the latest “Prioritized Central Corridor” area.

Unfortunately, American politics does not place a high value on truth, especially complicated, counterintuitive truths, and especially especially truths that people don’t want to hear like “we’re never going to fix congestion”.

Morgan-

There are certainly a good amount of half-truths and “inconvenient truths” out there. I guess the fact that you cannot build your way out of traffic congestion would also fall into your category of counter-intuitive truths. If more communities could accept this fact, they could get on with more productive pursuits.

If I was Lexington, I’d take that $272m, and put $27m/year towards more buses. That’s sufficient funding for about 55 more buses running 16 hours/day, 7 days/week. That doesn’t sound like much – but LexTran has a fleet of 79, so we’re talking a 70% increase in service – enough to boost their services to a 15-minute headway. That will do way more for ridership than a couple of 3-mile streetcar lines.

Tom-

Good point on the cost-effectiveness of buses. Streetcars, while they would definitely improve the transit access compared to the status quo, may not provide the transportation bang for their buck that buses do. But, they would help transform Lexington’s urban core (new development, higher property values) in a way that buses cannot.

Transitioning from a primarily road based transportation system to a public transit system is a long term process. What about the impact of self driving cars on reducing congestion (also a long term solution, in that it will probably take 10-30 years)? Would that be enough to make our road based system sustainable?

Andrew-

You’re right about the transition from a car-dependent city to a robust transit system being a long-term investment. The self-driving car possibility is intriguing but is not as preferable for 2 reasons:

1) No one really knows when or if this technology will become widely available, whereas creating a new transit system where one does not currently exist (while it can take decades) is a proven concept

2) If self-driving cars do become prevalent (again, no guarantees here), this would make roadway systems more efficiently used. But ultimately it would encourage more driving and more auto-dependence…not a sustainable outcome.