Last month (Sept. 14-16, 2015), I attended the Inner City Economic Summit in Detroit with Jeff Marcell, Senior Partner from our firm’s Seattle office. We spent the first part of the week in Detroit, engaging with leaders from other urban markets and national experts on the subject of inner city economies. Following the conference, we joined our clients at the East Michigan Council of Governments in Saginaw to share what we learned and to continue our work helping evaluate options for establishing a center of excellence. The work is part of the implementation phase of our prior engagement which resulted in a plan to boost economic development in the 8-county region centered on Saginaw.

The Inner City Economic Summit was created by the Initiative for a Competitive Inner City (ICIC), the Harvard-based think tank established by Michael Porter, and was sponsored by three other organizations: the W.E. Upjohn Institute for Employment Research, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, and the Economic Development Quarterly from Sage Publications. For those of you not familiar with the ICIC, it’s worth getting to know their organization and their work. My favorite aspect of the ICIC is their incredibly useful “library of best practices in urban economic development.” The summit was hosted at the Detroit Marriott Renaissance Center (the same complex where GM is headquartered) on Day 1 and at the Detroit branch of the Chicago Federal Reserve on Day 2. During both days, we heard presentations and panel discussions from national experts on urban economic development, including a keynote from Michael Porter. We learned first-hand about the unprecedented private sector investments centered on downtown and Midtown Detroit, led primarily by Rock Ventures. We also participated in a three-hour bus tour through several revitalized and distressed areas in Detroit. And at the end of the conference, we took our own “self-guided” tour of the most challenged neighborhoods before heading up to Saginaw for the second part of our Michigan visit.

The Summit was filled with high-quality presentations, panel discussions, and conversations with leaders from urban markets across the US. But three presentations rose to the top as the most insightful and relevant to the challenges and opportunities facing urban economic development (you can read a more detailed description of these three presentations at the bottom of this post):

1. Michael Porter, the famed Harvard economist and corporate strategy expert. Porter revisited 20 years of groundbreaking research and experience on inner city economies and their competitive advantages, reflecting on lessons learned and providing perspective on what’s next for the field.

2. Matthew Cullen, President and CEO of Rock Ventures. Cullen provided an in-depth perspective on how private sector investment has shaped Detroit’s infrastructure, economy, and culture in recent years.

3. Martin Lavelle, Business Economist with the Detroit branch of the Chicago Federal Reserve Bank. Lavelle shared an overview of Detroit’s current economic situation and offered perspectives on where it is headed, including some of the remaining barriers and potential pitfalls facing the city’s economy.

Throughout the summit, an underlying theme emerged during the discussions about Detroit’s economic future:

Does urban economic development need to be big or small?

I would argue that, in order for cities to have the greatest shot at success, their economic development programs must include a combination of big and small initiatives. Detroit is focusing on both ends of the spectrum, which is a good thing, given the serious challenges facing the city’s economic development. I’ll share with you the highlights from the summit, including what Detroit is doing to catalyze economic growth. But first, let me share a brief summary of how the city arrived at its current state of affairs. There are an infinite number of things that can be said about Detroit’s economic history (people have written lengthy essays and books about it), but I’ll be as short and to-the-point as possible. Here goes…

Detroit, Michigan played a leading role in the development of the US economy during the 20th century. It was the birthplace of modern manufacturing and large-scale industrial production. Henry Ford’s Model T (and the innovative assembly line that made it possible) transformed the global economy in ways that no one could have anticipated. Detroit was arguably the most important city in the world from 1900 to 1950, from an economic development perspective. The city was, and still is, the global epicenter of the automotive industry. Only a handful of US cities dominate a single industry in the same way (New York with finance, Houston with energy, and Los Angeles with film/entertainment). I’ve written more about Detroit’s status as the world’s automotive capital here. Detroit also occupies an important place in our nation’s cultural identity, thanks in large part to Motown.

But despite its many accolades, Detroit is better known today for its epic decline. Even though its business leaders and companies were responsible for revolutionizing the world’s economy, the city has become a universal symbol of economic failure. Detroit is the only city in US history to have reached the 1,000,000 mark in population and subsequently drop down below that mark. Even worse, Detroit came close to the 2,000,000 mark around 1950 (estimated at 1.85 million in 1950) before its population decline. Detroit is by no means the only US city where such a dramatic economic decline took place…but it is the by far the largest and most well-known. I’ve written more about Detroit’s population decline here. In 2010, the city’s population stood at 713,777. In 2013, the city entered the largest municipal bankruptcy in US history. The latest 2014 estimates for Detroit show a population of 680,250, less than 37 percent of its 1950 peak. And the city’s decline has taken place against a backdrop of racial inequities. With a city population that is 83 percent black and 11 percent white, compared with a metro area population that is roughly 70 percent white and 23 percent black, the city offers a glaring example of racial segregation. Interestingly, the city’s decline over the last several decades has played out within the context of a relatively stable metro area population. The Detroit metro area was home to 4,490,902 residents in 1970, compared with 4,296,611 in 2014, a decline of only four percent (compared with a 45 percent decline in the city’s population during the same period).

Although there are stark challenges facing Detroit’s economic future, there are some major signs of life in the city. Private sector investment, business expansions, and job growth are beginning to take place in portions of the city, especially in downtown and Midtown. Positive things are happening in Detroit on a level not seen in more than half a century. It’s too early to gauge whether these recent changes will turn the tide, but there is finally a reason to be optimistic about Detroit’s future. At the very least, it is an unprecedented experiment in urban economic development that will provide the rest of us with case studies and lessons learned for years to come. Hopefully those future lessons will be referred to as “best practices” instead of cautionary tales. Time will tell…

So, back to our question of whether urban economic development needs to be big or small: What does a struggling urban economy need to get back on track? What does Detroit need to change the course of its economy- many small things or a few big things?

Detroit has an aversion to big things. For nearly a century, their economy has been defined by big auto companies, big unions, and big government. All three of these big things have dramatically (and permanently) decreased. So it is understandable that many residents are placing their hopes of recovery in small things (e.g., block-by-block revitalization of Midtown, expansion of the Eastern Market as a local food hub, a new protected bike lane on Jefferson Avenue). On top of that, the city’s business and community leaders are equally concerned with pursuing larger, more transformative, strategies (e.g., the massive private sector investments from Dan Gilbert, a new streetcar line, the innovation/acceleration efforts lead by TechTown Detroit).

Below are three additional ideas for Detroit to consider as part of its “all of the above” approach to transform the local economy, each of which could potentially include a combination of big and small things:

1. R&D and higher education.

2. International development.

3. Aggressive business recruitment and expansion.

1. R&D and higher education. When we completed the Regional Prosperity Strategy last year for the 8-county region in East Central Michigan, one of the most surprising findings from our data analysis was how concentrated the academic R&D investments in Michigan are in the state’s top two schools. The University of Michigan in Ann Arbor is the nation’s number two institution ranked by academic R&D spending (nearly $1.4 billion in FY 2013). The state’s other top school and research powerhouse, Michigan State University in East Lansing, spent $516 million on R&D in FY 2013.Together, those two institutions account for more than 83 percent of Michigan’s total academic R&D expenditures.

While this is greatly beneficial for those institutions, it’s a huge missed opportunity for the rest of the state. In fact, Michigan has a higher percentage of academic R&D investments in its top two universities than the investments in the top two universities in the other top 10 states in the US ranked by total academic R&D expenditures. This is especially frustrating for the Detroit metro area which accounts for nearly half of the state’s population but less than 10 percent of the state’s academic R&D spending. Wayne State University in Midtown Detroit is the city’s only significant research institution, with $224 million in academic R&D investments in FY 2013. Wayne State is certainly playing a critical role in the revitalization of Midtown, thanks in large part to its 27,000 students and its nearly 6,000 employees, but it is still a far cry from being one of the world’s preeminent research universities.

The link between higher education and economic development is well-established. Besides the most prevalent examples (Stanford University in Silicon Valley, Harvard and MIT in Boston, and the University of Texas in Austin), dozens of communities across the US can trace their economic development success to the role of higher education. Which is why it’s no coincidence that Ann Arbor, just 40 miles from Detroit, is the best performing metro area in the state (along with Grand Rapids), having surpassed its pre-recession employment levels by 5 percent as of July 2015.

2. International development. With Windsor, Ontario right across the river from downtown, Detroit is part of the largest integrated, bi-national metropolitan economy in North America. Many people do not realize that the automotive manufacturing cluster centered on metro Detroit is actually a highly connected economic region that extends well into Canada. Given the city’s strong existing international ties, the multitude of nonstop international flights at Detroit-Wayne County International Airport, and the city’s global business connections, international business development represents a significant opportunity for Detroit.

3. Aggressive business recruitment and expansion. There is an untapped potential to bring in large private investment and business expansions from outside of Michigan into Detroit. An aggressive business recruitment program could play a large role in Detroit’s resurgence, while the city has a global brand and a reputation as an up-and-coming place for Millenials. The relocation of firms from Detroit’s suburbs into the urban core (e.g., Quicken Loans, Little Caesars) is wonderful for downtown, but the real opportunity lies in attracting new businesses from outside of the state. This won’t be easy, but business recruitment will be critical to the long-term growth of Detroit’s economy.

The beginning of something new? Or the beginning of the end?

This post could leave off on a positive note, citing once again the incredible transformation of downtown/Midtown Detroit. Or it could end on a less optimistic note, acknowledging the realities of a still-declining city that has yet to turn the tide. I’m going to do both.

Google Maps has a really cool new feature. You’ve probably used the Street View tool before, but you may not be aware that you can now use Street View to see the same photo perspective from multiple points in time. This is especially useful for cities that are experiencing rapid change, whether the change is positive or negative.

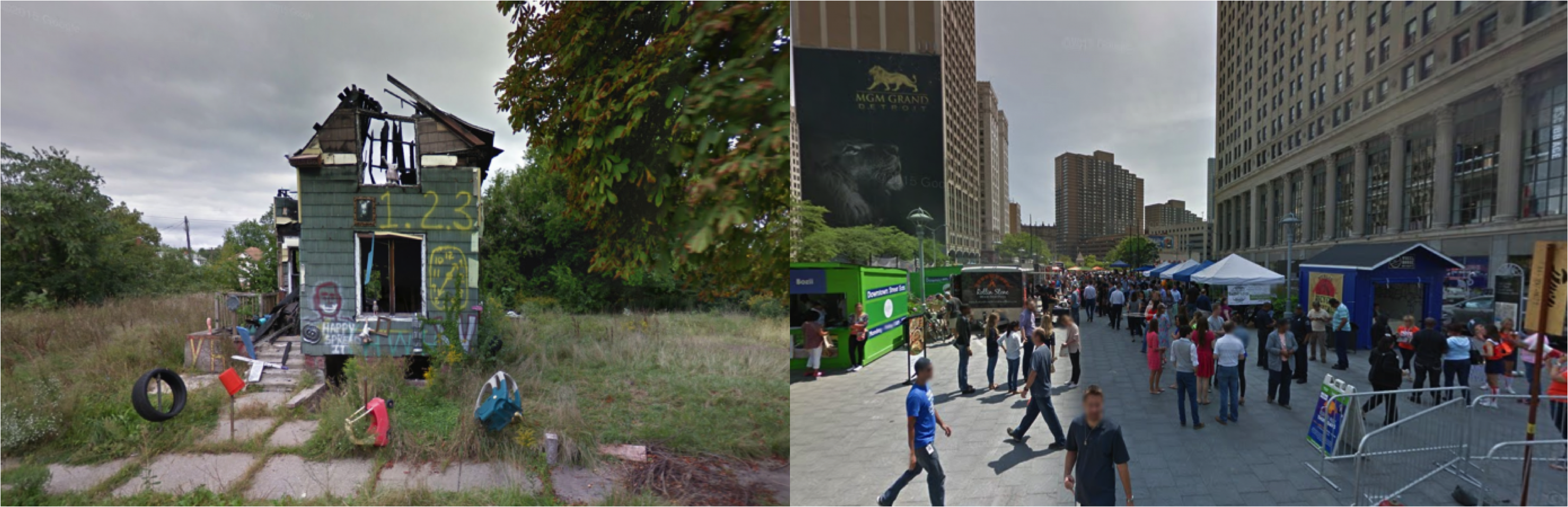

In Detroit’s case, I will leave you with two sequences of photos from Google’s StreetView. The first shows a house in the city’s near-East side neighborhood of McDougall-Hunt in 2009, 2011, and 2013. The second sequence shows Cadillac Square (just east of Campus Martius Park) in downtown Detroit in 2008, 2011, and 2015.

I’ll let the images speak for themselves.

House in east side Detroit neighborhood: June 2009

House in east side Detroit neighborhood: June 2011

House in east side Detroit neighborhood: September 2013

Cadillac Square in downtown Detroit: October 2008

Cadillac Square in downtown Detroit: June 2011

Cadillac Square in downtown Detroit: July 2015

Highlighted Inner City Economic Summit Presenter Summaries in Detail:

Michael Porter’s presentation was a comprehensive overview of the challenges and opportunities for inner cities, based on multiple decades of research and observation. It was fascinating, not only because Porter is a dynamic and incredibly knowledgeable speaker, but because he did a great job of tying the challenges facing inner city economic development to the realities in the larger national economy. You can download Porter’s presentation here [PDF]. You can also see a re-cap of his talk on YouTube. Porter began his talk by describing the structural challenges facing the US economy, concluding that “strengthening America’s inner cities has become more challenging due to the overall state of the US economy.” He contrasted this with the relatively strong national economy in 1990, back when ICIC was first getting off the ground. ICIC defines an inner city as “contiguous census tracts within central cities that are economically distressed”. Their definition of distressed is based on the following two criteria: 1) “a poverty rate of 20 percent or higher, excluding students” or; 2) “a poverty rate, excluding students, of 1.5x or more than the MSA” and at least one of two other criteria: “median household income 50 percent or less than the MSA” or “unemployment rate 1.5x or more than the MSA”. One of the more interesting points in Porter’s presentation was that inner city economic success is not closely correlated with overall metropolitan economic success. At first glance, this seems to go against commonly held beliefs that a strong inner city is needed for a strong metro economy. But Porter was also keen on pointing out that the central cities (not including the portions classified as inner city according to ICIC’s definition) accounted for all of the net job growth in the US from 2003 to 2013. He also shared several key findings about how to stimulate economic development in inner city economies, including: the importance of clusters as drivers of growth, connecting inner cities to regional clusters, and capitalizing on anchor institutions present in inner cities. While Porter’s talk touched on many of the challenges and opportunities facing inner city economic development, he did not cover one key area, real estate. Urban areas have many barriers impacting real estate development that don’t exist in suburban and exurban areas. Fortunately, the other keynote presentation from Matthew Cullen did cover real estate.

Matthew Cullen, head of Rock Ventures, also gave a dynamic keynote presentation. Rock Ventures is the umbrella entity created to manage Quicken Loans founder Dan Gilbert’s portfolio of 110 companies, investments, and real estate development projects in Detroit primarily, and to a lesser extent, in Cleveland. Cullen’s talk showcased the major transformations in downtown and Midtown Detroit, largely spearheaded by Rock Ventures and other private sector leaders (e.g., the Illitch family, which is bringing its Little Caesars corporate HQ from the suburbs into Midtown and is also building a new arena for the Red Wings hockey team as part of a new mixed-use district). It’s funny…at TIP we sometimes joke about the ”fairy godfather/godmother” strategy for downtown revitalization. As the story often goes, “all you have to do is find a rich/famous person with an affinity for your community, and then convince them to funnel millions of dollars into the renovation of historic buildings to create a bunch of cool new offices, restaurants, and loft apartments.” Well, downtown Detroit may be the best example ever of this strategy, with Dan Gilbert serving as Chief Executive Fairy Godfather and Matthew Cullen serving as Chief Operating Fairy Godfather. You can see Cullen’s presentation for yourself (parts 1 through 5 on YouTube), but I’ll give you the highlights. Since 2010, Rock Ventures has been responsible for the creation of 13,000 jobs, nearly $2 billion in investment, and the renovation/redevelopment of 13 million square feet of building space (office, residential, retail). They are also leading an effort to create a new $140 million streetcar line (with a remarkable $100 million coming from private and philanthropic investors, and only $40 million in public funds) that will connect downtown to Midtown after construction is completed in 2017. Rock Ventures has also invested in a downtown broadband internet infrastructure known as RocketFiber, which is purported to be 100x faster than Comcast. It’s pretty obvious that Gilbert’s efforts are starting to pay off in a major way. All it takes is a 10-minute walk through downtown Detroit, and you feel like you’re in an emerging hipster haven. Take another 20 minute walk north to Midtown, and you’ll find growing clusters of creative businesses like Shinola among the large anchor institutions of Wayne State University, the Detroit Medical Center, and the Detroit Institute of Arts. Lastly, Rock Ventures is keenly aware that bringing jobs and investment into the urban core will not create a vibrant district without a thoughtful approach toward improving the urban design, or the “connective tissue” as Cullen described it. Of course, it’s worth keeping in mind that, no matter how inspiring the work of Rock Ventures and other private sector leaders, the downtown/Midtown area only represents a small portion of Detroit, roughly 6 to 8 percent of the city’s land area, depending on how you define it. And when you consider the fact that the city’s urban core has seen a large amount growth (investment, job growth, and residential growth) while the city as a whole is still losing more than 8,000 residents a year (from 2010 to 2014), it is clear that the rest of the city is still declining rapidly. It will be interesting to watch the evolution of Detroit’s downtown/Midtown urban renaissance over the coming years. Hopefully, the success of the city’s urban core can translate into broader economic development for the rest of the city.

Martin Lavelle, an economist with the Detroit branch of the Chicago Federal Reserve Bank, gave a brief talk as part of the introductory set of presentations. (You can find his presentation at the tail end of this document.) I really appreciated Lavelle’s comments because he cut through the hype and gave a realistic assessment of where Detroit is and where it might be headed from an economic development perspective. Lavelle started by acknowledging the major progress in the city: improving city services, ongoing investment (largely in the downtown/Midtown area), a growing neighborhood focus, and a greater willingness among civic leaders to discuss the tough issues. Lavelle then went on to discuss some of the significant structural impediments that act as barriers to economic development in the city, most notably the lack of a premier research university and an inadequate public transportation system. He also highlighted several potential pitfalls that could send the city back into bankruptcy including: tax revenue declines, fiscal challenges facing other regional entities (e.g., Detroit Public Schools, Wayne County), and a potential return of corrupt elected leadership—a long-time hallmark of Detroit’s government. Finally, Lavelle touched on some of the key issues the city must tackle in order to become a prosperous community: reform of Detroit Public Schools, addressing the city’s many unique land use challenges, and regional cooperation.

Interesting read. One minor point though. Those pictures of the downtown park are actually of Cadilac Square Park, not Campus Martius. Campus Martius is just west of there.

Thank you, Tom. Good catch! The vantage point is between Campus Martius Park and Cadillac Square, but the view is of Cadillac Square. I’ve corrected this.

Just wanted to let you know that there’s a documentary on the market called The Great Detroit, It was-It is-It will be”. Some say its the finest documentary ever made about Detroit.

Its starts with how and why Detroit was founded to how it became a manufacturing powerhouse to the history of Motown, Techno, Eastern Market and so much more.

Well the film is available on amazon for your viewing pleasure.

Hi Anthony- Thank you so much! Will check this out.